Lever

Lever

A lever (or lever tumbler) is a lock design that uses flat pieces of metal (also known as levers) and a bolt as locking components. In this article, 'lever lock' does not mean a locking lever handle incorporating a cylinder locking device. In most designs, the position of the levers prevents the bolt from retracting. When positioned properly, a gate in the lever allows the bolt to move (shot or withdrawn). Lever locks are historically one of the most popular lock designs, but use has declined as less expensive pin-tumbler locks have gained popularity. Lever locks are popular in Europe (particularly the UK), eastern Europe, and some parts of South America, as residential and commercial door locks and on safes. Safe-deposit boxes in banks around the world use lever designs heavily.

History

A single locking tumbler was used on many Roman metal locks, often in association with wards. Many early door locks had no case, with a bolt and locking tumbler mounted on a backplate. From at least 13C, some locks had these components mounted in a wood stock without a backplate — this lock design is the Banbury lock (the reason for this name is unknown). These designs did not use fences and gates, but rather a simple pivoted tumbler or lever that the key had to move (typically, lift) out of the way in order for the bolt to move. Security was provided by warding. Other locks had a backplate mounted in a wood stock - the [plate] stock lock.

Barron lock

In 1778, Robert Barron patented [BP1200] the principle of all modern mechanical security locks — the double-acting movable detainer. His patent describes 'the gating or racking to allow a stump on the tumbler to pass through the bolt, or an opening in the tumbler to allow a stump on the bolt to pass through.' These two (of several possible) realisations of the double-acting movable detainer principle are now usually described as 'lever locks'. Barron's was the first lever lock that used a stump and gates. This technique requires each lever be moved to a precise distance (typically, height) at which the stump can pass through the gate. Overlifting or underlifting a lever leaves it blocking the stump - hence "Double acting"; older locks' levers only needed to be moved upwards to clear — more than that had no effect, as they had already cleared the obstacle. Barron, and after him his son, and others, used only the arrangement of stumps on the tumblers with gates in the bolt tail. This arrangement would prove in the long run less successful than Barron's other suggestion of a stump on the bolt tail and gates in the tumblers. The realisation Barron used is practically limited to 4 tumblers, and most locks had only 2. The other arrangement allows an unlimited number of levers to be stacked on the same pivot, blocking the same stump. The double-acting movable detainer principle is still in use to this day in lever locks, but also including pin-tumbler locks by Linus Yale, Jr.

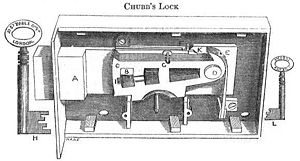

Chubb lock

In 1818, Charles and Jeremiah Chubb patented [BP4219] a lock design based on Barron's work. Their version used the placement of stump on the bolt tail and gates in the levers. These levers have 2 pockets, with the bolt stump moving through the gate in the lever fence (or bar) from one pocket to the other, as the bolt moves. This design is commonly associated with the name of Chubb, and is still in use today in many locks. They also added a device called the detector, an extra lever that triggered by overlifting of the main levers. When triggered, the detector would lock the bolt until it was reset [regulated, in Chubbs' word] with a special key. To make it more convenient to use, the Chubb detector lock was modified slightly in 1824 so that it could be reset by the working key, instead of a separate 'regulating' key. The concept of the ‘detector’ was that the lock not only responded to the true key, it also recognised a wrong key or picking attempt, and signalled this to the proper keyholder by a change of state. The concept was invented by Ruxton in 1816 [BP4027] but his realisation was not a practical success. The Chubb lock was the first to have a practical detector, combined with lever tumblers. Chubb later added false notches or serrations on the fences of the levers which prematurely bound components if tension were applied when the component was in the incorrect position. This anti-picking idea was originally introduced on Bramah locks from 1817, and also used on Anthony Strutt's lever lock of 1819 — the first to use end-gated levers. It was later included in security pins and many other lock designs. In 1820, Mallet patented a rotating barrel and curtain that closed off the keyhole when the key was turned and hindered independent movement of picking instruments. This addition helped to prevent decoding. De La Fons would later also be granted a patent for this same idea, in 1846. Although not widely used before 1851, the combined barrel-and-curtain are now commonly used security features of high-security lever locks - the name usually simply abbreviated to 'curtain'.

Tucker and Reeves

In 1851, a new design surfaced with a bolt that was not rigidly fixed but could shift on one end. Patented by Tucker and Reeves, this design aimed to thwart picking attempts involving pressure on the bolt. The shifting bolt made it harder to feel the gates inside the lock as it shifted. In 1853, the design was refined to include a rotating barrel that prevented movement of the bolt until a key was inserted.

Parsons lock

Another form of ‘lever’ lock was Thomas Parsons’ balance lock [BP8350] of 1832. This originally had a plurality of levers pivoted around their midpoint (earlier levers were pivoted at one endpoint) below the bolt tail, each lever having a hook (of differing lengths) at both ends. Spring pressure pressed the hooks at one end into a notch in the bolt tail, (locking the bolt against movement). The key steps pushed on the other ends of the levers. The key bit pressed those ends towards the bolt, which had notches for these hooks also. (There are two notches each end of the bolt tail, for the shot and withdrawn positions of the bolt.) The correct key balanced every lever with neither end hooking into the bolt. Because the balance levers take little strain, they can be thin, so that using 7 was common, and up to 20 in some safe locks. This linear lock enjoyed considerable success in the 19th C. A cylinder locking device version made by CAWI appeared in 1951, using essentially the same idea, differently realised.

Numerous detail variations in the lever mechanism have been invented. Levers may be arranged to slide rather than pivot. The bolt tail may be within the lever stack (typically, in the middle). Levers all on one pivot may be arranged to pivot in opposite directions (typically, alternate levers). Or there may be a plurality of lever stacks, and a plurality of stumps. Such locks are mainly used for high grade safes.

Several anti-pressure devices, and other pick-resisting features, have been invented.

There have also appeared several lever cylinder locking devices, of which the Ingersoll Impregnable is notable. It has been made under licence in the USA by Sargant & Greenleaf.

'Simple' should not be equated to 'insecure'. Designs using a double-bitted key with unsprung levers having closed bellies, cheaply made in zinc alloy castings, are widely-used on medium-grade safes in Europe. Lever steps on one bit move the levers, the corresponding steps on the other bit stop the levers moving too far. The levers are end-gated, (allowing a strongly-fixed and well-supported bolt stump) with numerous serrated false notches. Locks of this type are practically impossible to pick tentatively, and inside a safe door are well-protected against force. Usually, re-lockers are also connected, to frustrate disrupting the lock by force or explosive.

Many lever locks are less demanding of production precision than cylinder locks, and this has increased the popularity of physically robust lever locks in eastern Europe in the past few decades.

Principles of Operation

Although this describes the typical arrangement, several other realisations also occur.

A stack of levers is placed in the lock. Every lever must be properly moved (typically raised) by the key to allow the bolt stump fixed to the bolt tail to pass through the gates of the levers, retracting or extending the bolt. Each lever may have a different sized belly, or a different gate position to provide differs.

See also: Detainer Levers

Components

- Levers

- The primary locking component of lever lock. Each lever is a flat piece of metal with a gate which must be moved to the proper position to allow the stump to pass through and retract or extend the bolt. Each lever is normally impelled by a spring, usually fixed to the lever. Some levers use a thinned belly section referred to as "conning" to ensure the lever interfaces with the correct bitting area on the key.

- Stump

- The stump is a protrusion usually fixed to the bolt. The stump prevents the bolt from being extended or retracted until the levers are properly positioned. Traditional designs have the stump and levers interconnected (pockets are closed, with the stump sitting inside each lever).

- Washers

- Washers are flat (often metal) plates placed between each lever to ensure that each lever is properly raised by each bitting cut. They are not universal, but common in outdoor facing lever locks that require a high degree of reliability, especially in harsh conditions. On some cheaper locks they are replaced by stamped bumps which maintain the spacings without increasing the parts count.

- Barrel and Curtain (now combined and usually referred to simply as 'curtain')

- This is a component used in the keyhole to help prevent direct access to the levers after the key or pick is rotated in the lock. When the key turns, the curtain blocks the keyhole. The barrel hampers the independent movements of a 2-in-1 pick of the design originally used by A C Hobbs. This protects against casual manipulation of the levers, but does not preclude lockpicking attacks completely.

Vulnerabilities

Lever locks (in common with other locks) are vulnerable to a variety of attacks, depending on their design. Tentative picking is increasingly difficult as the number of levers increases. Many security locks also incorporate features which hamper manipulation, and additionally, warding is also sometimes used to this end (just as in pin tumbler locks). Tools to pick and decode lever locks are not as widely available as their pin-tumbler counterparts, largely because the tools required are more laborious to make, and expensive, and are more likely to be specialized to each lock, unlike pin tumbler and wafer tumbler picks. However, devices do exist and can be effective. Often, more specialised tools are made for a size and design for an individual model of lever lock. In general, well-made lever locks incorporating several pick-resisting features are likely to be physically stronger and more resistant to manipulation than comparable pin tumbler cylinder locks. They are likely to be larger, and typically have slightly larger keys. Lever locks in widespread use tend to have fewer differs than comparable pin tumbler cylinder locks, although trial of keys is hindered by the greater weight of keys needed and the slower rate at which they can be tested. Keys for different models of lever locks have a considerable variety of sizes, further impeding trial of keys.

One- and two-level masterkeying is used for small suites, and has been much used in institutions in the past. Most lever locks are not well-suited to complex large-scale or multi-level masterkeying. Those with Detainer Levers are generally better for this than those with H gate levers.

Many security lever locks are well-protected against drilling, so that this attack usually needs more work than most pin tumbler cylinders. Drill points vary from one lock model to another and are not visible externally. Lever locks, especially those with a protective curtain, are highly resistant to severe weather conditions.

Notes

- Lever locks are not subject to key bumping or pick gun attacks.

References

PULFORD, Graham (2007). High Security Mechanical Locks: An Encyclopedic Reference. ISBN 0750684372.